Opioid Tolerance Calculator

Estimate your current tolerance level and understand potential risks based on your medication history. This tool provides educational information only, not medical advice.

When you first start taking opioids for pain, they work. You feel relief. But after weeks or months, that same dose doesn’t help as much. So your doctor increases it. Then again. And again. This isn’t a mistake. It’s opioid tolerance-a normal, predictable change in your body’s response to the drug. It doesn’t mean you’re addicted. It doesn’t mean you’re weak. It means your nervous system has adapted.

What Exactly Is Opioid Tolerance?

Opioid tolerance happens when your body gets used to the drug. Over time, the same amount of medication stops doing what it used to. If you were getting pain relief from 10 milligrams of oxycodone, now you need 20. Or 30. That’s not because your pain got worse. It’s because your brain and nerves changed how they respond.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) defines tolerance as a physiological shift-your body adapts to the presence of the drug, and its effects become weaker. This isn’t unique to opioids. It happens with caffeine, alcohol, even some antidepressants. But with opioids, the stakes are higher. A small increase in dose can mean the difference between comfort and danger.

How Does Your Body Build Tolerance?

At the core of opioid tolerance is the mu-opioid receptor, or MOR. This is the main target for drugs like morphine, oxycodone, and fentanyl. When you take an opioid, it binds to these receptors, blocking pain signals and triggering dopamine release-that’s the feeling of relief or even euphoria.

But when the drug is around all the time, your cells don’t like it. They respond by:

- Reducing the number of receptors on the cell surface (downregulation)

- Changing the receptors so they don’t respond as strongly (desensitization)

- Shutting down the internal signaling pathways that once made the drug effective

Studies in the Experimental and Therapeutic Medicine journal show this isn’t just about receptors. Inflammation plays a role too. Proteins like TLR4 and NLRP3 inflammasomes get activated by long-term opioid use, making your nervous system more sensitive to pain and less responsive to the drug. The more you take, the more your body fights back.

And here’s the tricky part: tolerance doesn’t develop at the same rate for every effect. You might lose pain relief quickly, but still be at risk for breathing problems at the same dose. That’s why increasing your dose doesn’t always make you safer-it can make you more vulnerable to overdose.

Tolerance vs. Dependence vs. Addiction

People often mix up tolerance, dependence, and opioid use disorder (OUD). They’re related, but not the same.

Tolerance is about reduced effect. You need more to get the same result.

Dependence is about withdrawal. When you stop taking the drug, your body goes into shock. You sweat, shake, feel nauseous, have trouble sleeping. That’s your nervous system trying to rebalance after being flooded with opioids for so long.

Opioid use disorder is when your use starts controlling your life. You keep taking it even though it hurts your relationships, your job, your health. You might lie, steal, or risk overdose just to get more.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) is clear: tolerance alone doesn’t mean you have an addiction. But it’s a major stepping stone toward it. And if you’re on long-term opioids, you’re very likely to develop tolerance. Studies show about 30% of patients on chronic opioid therapy need higher doses within the first year.

Why Dose Increases Are Dangerous

Every time you increase your dose, you’re moving closer to the edge. Higher doses mean higher risk of respiratory depression-the leading cause of opioid overdose death. And here’s the cruel twist: the more tolerant you become, the more likely you are to underestimate how much you can safely take.

That’s especially dangerous with street drugs. Fentanyl, a synthetic opioid 50 to 100 times stronger than morphine, is now mixed into counterfeit pills and powders. Someone who’s built up tolerance to prescription oxycodone might take a pill thinking it’s the same strength. But if it’s laced with even a tiny bit of fentanyl, it can stop their breathing in seconds.

The DEA reports that fentanyl potency can vary by 50-fold within the same batch. There’s no way to tell. No test strip can fully protect you. That’s why overdose deaths involving synthetic opioids jumped to over 81,000 in 2022 in the U.S. alone.

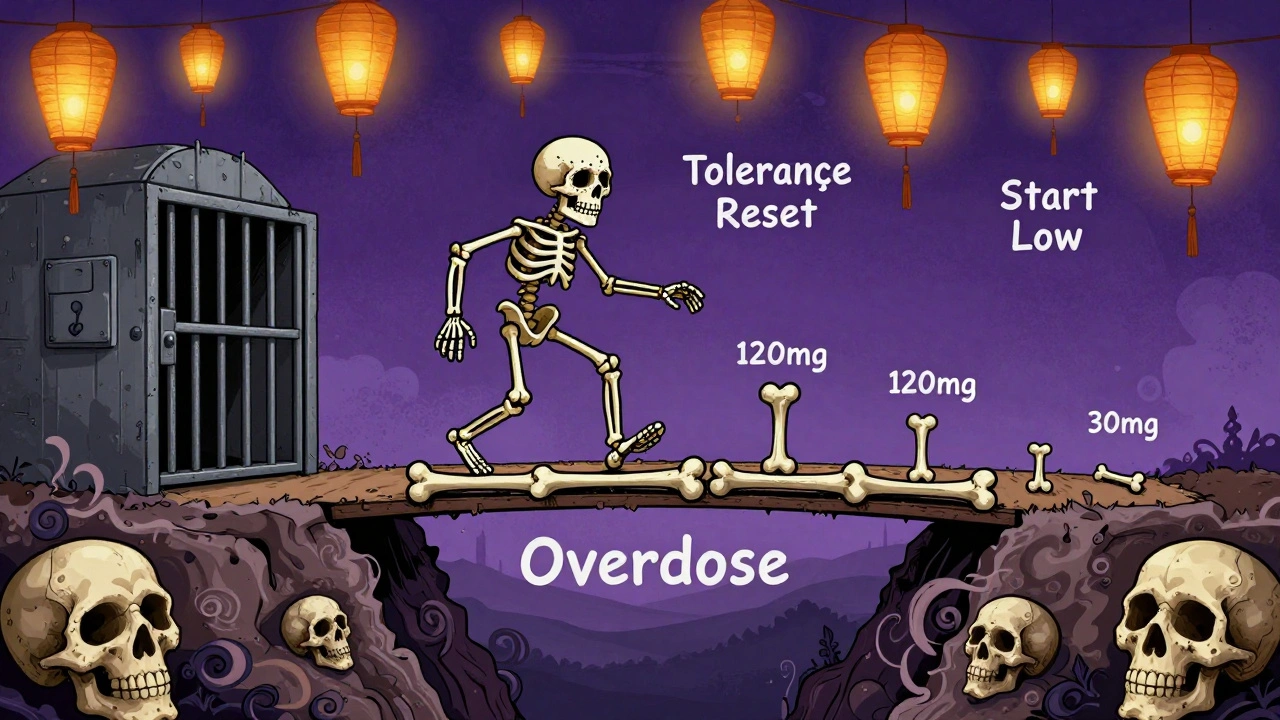

The Hidden Risk: Losing Tolerance

One of the most overlooked dangers isn’t taking too much-it’s taking too much after not taking any at all.

If you stop opioids for any reason-rehab, jail, surgery, or just deciding to quit-your body starts to reset. Your receptors come back. Your sensitivity returns. Your tolerance drops. Fast.

That’s why 74% of fatal overdoses among people with opioid use disorder happen in the first few weeks after release from prison. Someone who was taking 120 mg of oxycodone daily might spend three months in jail without access. When they get out, they go back to their old dose. Their body can’t handle it anymore. They overdose.

Research from Wakeman et al. (2020) shows that 65% of overdose deaths in recovery involved people returning to previous doses without adjusting. No one tells them: “Your tolerance is gone. Start low.”

How Doctors Manage Tolerance

Good doctors don’t just keep increasing doses. They look for alternatives. The CDC recommends that before raising daily opioid doses above 50 morphine milligram equivalents (MME), providers should:

- Reassess treatment goals

- Consider non-opioid options like physical therapy, nerve blocks, or certain antidepressants

- Check for signs of misuse or mental health conditions

Some doctors use opioid rotation-switching from one opioid to another (like from oxycodone to methadone). This can reset tolerance because different drugs bind to receptors in slightly different ways.

There’s also emerging research on combination therapies. Early trials using low-dose naltrexone (a drug that blocks opioid receptors) alongside opioids show promise. In some studies, patients needed 40-60% less opioid over time because the naltrexone helped prevent tolerance from building.

And yes, blood tests can help. They don’t diagnose tolerance, but they can show if someone is taking their medication as prescribed-or if they’re taking more than they say.

What You Can Do

If you’re on long-term opioids:

- Ask your doctor: “Is this still the best option for me?”

- Don’t skip appointments. Tolerance doesn’t happen overnight. Regular check-ins help catch problems early.

- Keep a pain diary. Note what helps, what doesn’t, and how your mood changes.

- If you’ve stopped opioids-even for a few days-never go back to your old dose. Start at 25-50% of what you used to take.

- Keep naloxone (Narcan) on hand. It’s free in many places and can reverse an overdose.

If you’re helping someone else:

- Don’t assume they’re addicted because they need more medication.

- Encourage them to talk to their doctor about alternatives.

- If they’re in recovery, remind them: tolerance is lower now. Start small.

The Bigger Picture

Opioid tolerance isn’t a failure. It’s biology. And it’s one of the main reasons the opioid crisis keeps growing. Every time a doctor prescribes opioids for chronic pain without a clear exit plan, they’re setting up a cycle: pain → relief → tolerance → higher dose → more risk.

The FDA now encourages drug makers to develop new painkillers that don’t cause tolerance. Researchers are exploring anti-inflammatory drugs that might block the brain’s reaction to opioids before tolerance kicks in.

But until those drugs arrive, the best tools we have are awareness and caution. Know that tolerance is normal. Know that higher doses aren’t always better. And know that if you’ve stopped, your body has changed. You’re not the same person you were six months ago. Your tolerance isn’t the same. And if you go back to your old dose-you might not come back at all.

Is opioid tolerance the same as addiction?

No. Tolerance means your body needs more of the drug to get the same effect. Addiction, or opioid use disorder, means you can’t control your use despite harm. You can have tolerance without addiction. But tolerance often leads to addiction if doses keep rising and no alternatives are explored.

Can you develop tolerance to opioids in just a few weeks?

Yes. Some people notice reduced pain relief within two to four weeks of regular use. Others may take months. It depends on genetics, metabolism, how often you take the drug, and the dose. There’s no set timeline-it varies by person.

Does tolerance mean the medication isn’t working anymore?

Not necessarily. It means the original dose isn’t enough. But increasing the dose isn’t always the answer. Sometimes, switching medications, adding non-opioid treatments, or reducing frequency works better. Tolerance doesn’t mean you’re out of options-it means you need a new plan.

Why is tolerance dangerous with street drugs like fentanyl?

Street drugs are unpredictable. A pill that looks like oxycodone might contain fentanyl-50 to 100 times stronger. Someone with tolerance to prescription opioids might take a dose they think is safe, but it’s actually lethal. Fentanyl’s potency makes it easy to overdose, especially if you don’t know what you’re taking.

If I stop opioids for a while, will my tolerance go away?

Yes. Tolerance drops quickly after stopping. Within days to weeks, your body regains sensitivity. That’s why overdose risk spikes after rehab, jail, or a break from use. Never return to your old dose. Start with a fraction-25% or less-and go slow.

Are there alternatives to increasing opioid doses?

Yes. Physical therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy, nerve blocks, acupuncture, and certain non-opioid medications like gabapentin or duloxetine can help manage chronic pain. Some patients find relief by reducing opioid doses and combining them with these treatments. Talk to your doctor about a plan that doesn’t rely on higher doses.

There are 11 Comments

Shubham Pandey

Been on oxycodone for 3 years. Dose doubled twice. Still hurts. Guess biology wins.

Elizabeth Farrell

I just want to say how important it is to recognize that tolerance isn’t a personal failure-it’s a physiological reality. So many people feel shame when their body adapts, but that’s like blaming your kidneys for filtering too much water. Your nervous system isn’t broken, it’s trying to survive. If you’re reading this and you’re on long-term opioids, please don’t isolate yourself. Talk to your doctor about alternatives. Try physical therapy. Even small movements can rewire pain signals. And if you’ve ever stopped and then restarted? Please, please start low. Your life matters more than pride.

Paul Santos

Interesting how the FDA’s definition of tolerance is essentially a rebranding of neuroadaptation-classic bureaucratic euphemism. The mu-opioid receptor downregulation is just one facet of a broader epigenetic recalibration, my friends. And let’s not ignore the TLR4/NLRP3 inflammasome cascade-this isn’t just pharmacokinetics, it’s immunoneurology in action. 🤓

Eddy Kimani

Wait-so if tolerance develops faster than dependence, does that mean the body can adapt to the drug’s effects before it becomes physically reliant? That’s wild. I’ve read about receptor internalization, but the inflammasome angle is new. Anyone know if there are biomarkers we can track to predict tolerance onset? Like cytokine levels or receptor density via PET scans?

Chelsea Moore

Oh my GOD. This is why we can’t have nice things. People take pills like candy, then cry when they get addicted. It’s not the drug’s fault-it’s their weakness! Why are we coddling people who can’t handle a little pain? You think your back hurts? Try raising kids on minimum wage! This post is just enabling addiction!

ruiqing Jane

Thank you for writing this with such clarity. I’ve watched three friends spiral because doctors kept prescribing higher doses without ever asking, ‘What else could help?’ One of them is now in recovery-and she says the hardest part wasn’t quitting. It was realizing no one told her that tolerance resets. She went back to her old dose after rehab. She didn’t make it. If you’re reading this: please, don’t wait until it’s too late. Ask for alternatives. Keep naloxone. And if you’re helping someone-remind them they’re not broken. Their body just learned to survive. That’s not weakness. That’s wisdom.

John Webber

my doc just keeps givin me more and more and i dont even know why anymore. i think i might be addicted but im scared to say it. everyone says its just tolerance but i dont feel right anymore

Sheryl Lynn

Oh, darling, let’s not pretend this is just ‘biology.’ This is the pharmaceutical-industrial complex feeding off chronic pain like a vampire at a buffet. They sold us pills as a quick fix, then watched us spiral into tolerance, dependence, and overdose-all while raking in billions. The real villain isn’t your receptors. It’s the $500 billion industry that never wanted you to heal. It wanted you to keep buying.

Genesis Rubi

USA got the best medicine in the world but now we’re all on opioids? What’s next, painkillers for sadness? We’re getting soft. In my country we just grin and bear it. If you can’t handle pain, you’re not American enough.

Doug Hawk

Just wanna say the part about tolerance dropping after jail or rehab hit me hard. My brother did 8 months and came back and took his old dose. He didn’t wake up. Nobody warned him. No one told him his body changed. I wish someone had told us. Now I carry Narcan everywhere. And I tell everyone I know: if you stop, start at 25%. Please.

John Morrow

Let’s be brutally honest: tolerance is the first domino in a cascade of self-destruction. The moment your body adapts, you’ve entered the slow-motion suicide of dose escalation. Every milligram increase is a gamble with your respiratory center. And the irony? The very mechanism meant to protect you-receptor downregulation-is the same one that makes you more vulnerable to overdose when you relapse. This isn’t medicine. It’s a slow, bureaucratic death sentence disguised as care. And the worst part? The system knows. They’ve known for decades. And they still keep writing scripts.

Write a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *