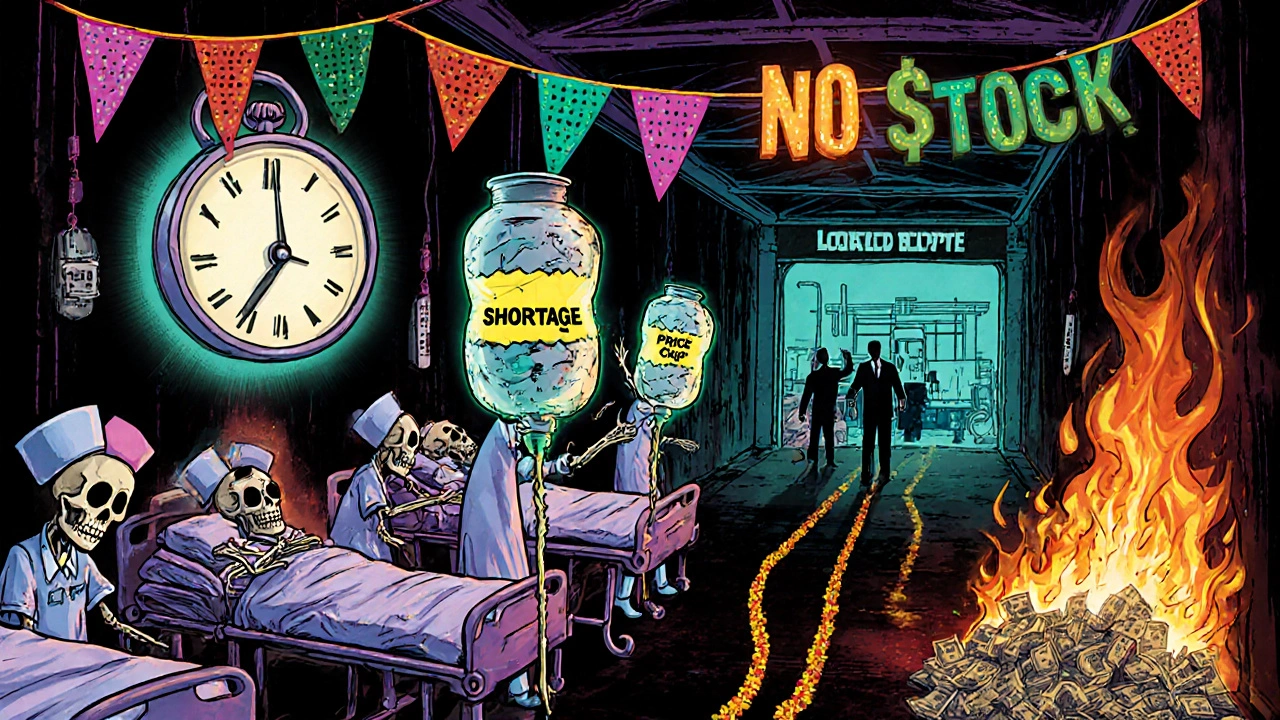

When you walk into a pharmacy and find your regular medication is out of stock, or your GP says they can’t get the blood pressure pills you need, it’s not just bad luck. It’s the result of pricing pressure and shortages tearing through the healthcare system - and the economic fallout is hitting patients, providers, and budgets hard.

These aren’t new problems, but they’ve gotten worse since 2020. The pandemic didn’t create them - it exposed them. When global supply chains snapped, when factories shut down, when shipping containers piled up at ports, healthcare didn’t escape. Drugs, medical devices, even basic supplies like IV bags and syringes started vanishing. At the same time, demand didn’t drop. People still got sick. Chronic conditions didn’t pause. Hospitals kept running. And when supply can’t keep up, prices rise - fast.

Why Healthcare Shortages Hit Harder Than Other Sectors

Not all shortages are the same. If you can’t buy a new TV, you wait. If you can’t get insulin, you don’t wait. Healthcare goods are inelastic - people need them, no matter the cost. That’s why when shortages hit, prices don’t just creep up - they spike.

Take the case of generic injectable drugs. In the U.S., the FDA recorded over 300 active drug shortages in 2022, many of them life-saving medications like chemotherapy agents and antibiotics. In the UK, the NHS reported similar patterns. A 2023 analysis by the Office for Health Economics found that 42% of commonly prescribed generic drugs had experienced at least one supply interruption in the previous 18 months. The result? Prices jumped an average of 28% for those drugs, with some rising over 100%.

Why? Because when one manufacturer can’t produce enough, others can’t instantly fill the gap. Many generic drugmakers operate on razor-thin margins. They don’t have spare capacity. They don’t stockpile raw materials. When a supplier in India or China faces a regulatory delay, a power outage, or a labor strike, the entire chain breaks. And because these drugs are sold at fixed prices under public health contracts, providers can’t just raise their charges to cover costs - so they ration. Patients get fewer doses. Clinics delay treatments. Some go without.

The Hidden Cost: How Pricing Pressure Drives System-Wide Inflation

Pricing pressure doesn’t just mean higher drug bills. It ripples through the entire system.

Hospitals pay more for supplies, so they cut back on staff hours, delay equipment upgrades, or reduce non-urgent services. A 2023 survey of 120 NHS trusts in England found that 68% had reduced elective surgery volumes due to supply-related cost increases. That’s not just a service issue - it’s a public health delay. People waiting longer for hip replacements, cancer screenings, or heart procedures face worse outcomes.

And it’s not just drugs. Medical devices like ventilators, infusion pumps, and even basic monitoring equipment faced similar bottlenecks. One Leeds-based hospital reported a 6-month wait for replacement pulse oximeters in late 2021. Staff had to reuse devices beyond recommended lifespans. That’s not just risky - it’s expensive. The cost of a single infection caused by a faulty or overused device can run over £5,000 in added care. Multiply that across hundreds of cases, and you’re talking millions in avoidable spending.

The Cleveland Federal Reserve’s research shows that supply shocks raise prices more than demand shocks - and in healthcare, the effect is amplified. A 1% supply disruption in essential medical inputs can drive up healthcare inflation by 0.3-0.5%, compared to just 0.05% for non-essential goods. That’s because healthcare is already a high-cost sector with little room for substitution. You can’t swap insulin for aspirin. You can’t replace a heart stent with a bandage.

Who Pays the Price? Patients, Providers, and Taxpayers

When prices rise and supplies vanish, the burden doesn’t fall equally.

Patients with chronic conditions - diabetes, hypertension, epilepsy - are hit hardest. Many rely on the same drug, every day, for life. When it disappears or costs 3x more, they skip doses. They switch to less effective alternatives. They end up in emergency rooms. A 2022 study in the British Medical Journal found that patients who missed doses due to cost or availability had a 41% higher rate of hospital admission within six months.

Providers are squeezed too. Clinics and community health centers, especially in rural areas, have less negotiating power than big hospitals. They can’t buy in bulk. They can’t lock in long-term contracts. When a supplier raises prices suddenly, they have to choose: absorb the cost (and lose money), pass it on (and lose patients), or go without (and lose trust).

Taxpayers foot the bill through public health spending. In the UK, the NHS spent £1.2 billion more on pharmaceuticals in 2022 than in 2019 - not because more people were sick, but because the same drugs cost more. The Office for Budget Responsibility estimated that supply chain-driven inflation in healthcare added £3.1 billion to public health spending between 2020 and 2023. That’s money taken from mental health services, community care, and prevention programs.

Why Price Caps Make Shortages Worse

It sounds fair: cap prices to protect patients. But in practice, price controls often make shortages worse.

The UK’s energy price cap in 2021 kept household bills down - but it caused 27 energy suppliers to collapse because they couldn’t cover their costs. The same logic applies to drugs. When governments set fixed reimbursement rates for generic drugs, manufacturers have no incentive to keep producing them if their costs rise. Why invest in a product you can’t profit from?

Harvard economist Martin Weitzman showed this pattern clearly: when prices are held artificially low, consumers don’t just buy more - they hoard. When a drug is rumored to be going out of stock, patients and even pharmacies start stockpiling. That creates artificial scarcity. The very policy meant to protect people ends up accelerating the shortage.

One NHS trust in Yorkshire reported a 70% spike in prescriptions for metformin in a single month - not because more people were diagnosed with diabetes, but because patients were buying three months’ supply at once, fearing future shortages. The result? The next month, the drug vanished from shelves entirely.

What’s Being Done - And What’s Not

Some solutions are working. The European Commission allowed temporary relaxation of competition rules in 2021 so that pharmaceutical companies could share production capacity. In Germany, that cut drug shortages by 19% in six weeks. The U.S. FDA started publishing real-time shortage alerts and fast-tracking approvals for alternative suppliers. In the UK, the Department of Health began requiring manufacturers to report potential supply risks six months in advance.

But these are bandaids. The real fix requires structural change.

First, diversify supply chains. Relying on one country for 80% of your active pharmaceutical ingredients is a gamble. Countries like India and China dominate production - but they’re vulnerable to political shifts, climate events, and regulatory crackdowns. Companies that built dual sourcing - using suppliers in Europe and North America as backups - saw 35% fewer disruptions, according to a 2022 McKinsey study.

Second, build inventory buffers. Hospitals and pharmacies need strategic reserves - not just for pandemics, but for routine disruptions. That costs money upfront, but it saves far more in avoided emergency purchases and patient harm.

Third, reward manufacturers for reliability, not just low cost. Public health contracts should include penalties for chronic shortages and bonuses for consistent supply. Right now, the system punishes the companies that invest in resilience.

The Road Ahead: More Fragility, Not Less

The good news? Global supply chain pressure has eased since late 2022. The San Francisco Federal Reserve’s Global Supply Chain Pressure Index returned to pre-pandemic levels by early 2023. Inflation in healthcare goods has slowed.

The bad news? The underlying risks haven’t gone away. Geopolitical tensions, climate disruptions, and labor shortages in manufacturing are still active. The International Monetary Fund warns that supply chain pressures will remain 15-20% above pre-pandemic levels through 2025. Climate-related factory shutdowns in Southeast Asia, port strikes in Europe, and rising energy costs for chemical production are all looming threats.

And as demand grows - with aging populations, rising chronic disease, and expanded health coverage - the system will face even more strain. We’re not returning to normal. We’re entering a new normal: one where shortages and pricing pressure are constant, not exceptional.

That means patients, providers, and policymakers need to stop treating these as temporary crises. They’re structural features of the modern healthcare economy. The only way forward is to build resilience into the system - not just with emergency fixes, but with smarter contracts, diversified suppliers, and smarter inventory. Because next time, there won’t be a pandemic to blame. Just a system that didn’t adapt.

Why do drug shortages happen even when there’s enough global production?

Global production doesn’t mean local availability. Many generic drugs are made in just one or two factories. If one plant shuts down for regulatory issues, a power outage, or labor strike, there’s no backup. Supply chains are designed for efficiency, not resilience. Companies don’t keep spare capacity because it’s expensive - and they’re paid low prices, so they can’t afford it.

Can price controls prevent healthcare inflation?

Price controls can delay price increases, but they often make shortages worse. When manufacturers can’t raise prices to cover rising costs, they stop making the product. That’s what happened with 27 UK energy suppliers in 2021 - and the same pattern shows up with generic drugs. Patients end up with no access, not lower prices.

Are shortages getting better or worse?

Shortages have eased since 2022, but the underlying risks are growing. Climate change, geopolitical instability, and labor shortages in manufacturing mean disruptions are more likely to happen again. The IMF predicts supply chain pressures will stay 15-20% above pre-pandemic levels through 2025. The system is more fragile now than before.

How do shortages affect patient outcomes?

They directly harm health. A 2022 BMJ study found patients who missed doses due to shortages had a 41% higher chance of hospital admission. Delays in cancer treatments, insulin shortages for diabetics, and antibiotic shortages for infections all lead to worse outcomes - and higher long-term costs.

What can individuals do when their medication is unavailable?

Don’t stop taking your medication without talking to your doctor. Ask if there’s an alternative brand or formulation. Contact your local pharmacy to check other branches. Some NHS regions have emergency supply networks for critical drugs. And report shortages to your local health authority - tracking these helps push for systemic fixes.

There are 10 Comments

ASHISH TURAN

Been there. My dad’s on metformin, and last year we went three weeks without it. Pharmacy said it was 'temporary.' Temporary turned into a nightmare. We had to switch to a different brand that gave him stomach issues. No one in the system seemed to care until he ended up in the ER. This isn’t policy debate-it’s people starving for pills they’ve taken for 15 years.

Ryan Airey

Let’s cut the crap. This isn’t a supply chain issue-it’s a capitalist failure. Generic drug makers are profitable *only* when they’re allowed to gouge. The moment prices are capped, they play chicken with patient lives. Meanwhile, CEOs take bonuses while hospitals ration insulin. Fix the profit motive, not the logistics. The system is designed to fail people. It’s not broken-it’s working as intended.

Hollis Hollywood

I’ve worked in a rural clinic for 12 years, and I’ve seen this play out in slow motion. It’s not just about the drugs-it’s about the emotional toll. You watch someone cry because they can’t afford their blood pressure med, and you have zero power to fix it. You start to feel like a fraud. The FDA alerts help, but they don’t bring back the trust. When patients stop believing the system will show up for them, that’s when the real damage begins. We’re not just losing inventory-we’re losing faith.

Aidan McCord-Amasis

Drug shortages? 😒 Same old, same old. We need a new system. Not more reports. Not more 'studies.' Just fix it. 🤷♂️

Adam Dille

Big picture: we’re all stuck in this mess together. I get why manufacturers cut corners-low margins, high risk. But we’re also asking them to be heroes without giving them tools. What if we paid a little more for reliability? Like, actually rewarded companies that never run out? Maybe then we wouldn’t have to pray every time we refill a prescription. Just a thought.

Katie Baker

I’m so glad someone finally wrote this. I’ve been telling my friends for years that if you’re on a chronic med, you’re basically playing Russian roulette with your health. I just hope this gets more attention. We can do better. We *have* to.

John Foster

There’s a metaphysical dimension to this crisis that no one dares to name. The modern healthcare system doesn’t just fail to deliver pills-it fails to honor the sacredness of human survival. We’ve reduced life-saving substances to commodities on a Bloomberg terminal, and in doing so, we’ve severed the moral contract between caregiver and patient. The shortage isn’t of drugs-it’s of reverence. When a man needs insulin and finds none, he doesn’t just face hyperglycemia-he faces the collapse of meaning itself. And we, the collective, have become numb to it.

Edward Ward

Wait-so if we diversify supply chains, build buffers, and reward reliability, we’re not just fixing shortages-we’re rebuilding trust in the system? That’s actually… kind of beautiful. But here’s the catch: who pays for that? If we make manufacturers accountable, we need to make *payers* accountable too. Hospitals, insurers, governments-they all play a role. Why is it always the patient who gets squeezed? And why does no one ever talk about the fact that we’ve outsourced production to countries with zero regulatory transparency? It’s not just greed-it’s negligence disguised as efficiency.

Andrew Eppich

It is not the role of government to subsidize corporate inefficiency. If a manufacturer cannot produce a drug profitably under current pricing structures, then it should exit the market. Patients should not be entitled to specific medications; they should be entitled to care. There are alternatives. There are always alternatives. The problem is not scarcity-it is entitlement.

Jessica Chambers

Oh, so now we’re blaming the system? 😏 I thought it was just bad luck. Next you’ll tell me the moon causes the insulin shortage too. 🌙💊

Write a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *