AERD Medication Safety Checker

Enter any medication name to check if it's safe for people with Aspirin-Exacerbated Respiratory Disease (AERD). This tool is based on clinical guidelines for AERD patients.

Aspirin-Exacerbated Respiratory Disease (AERD) is a chronic condition that links three distinct problems: asthma, chronic sinus disease with nasal polyps, and a heightened reaction to aspirin and other non‑steroidal anti‑inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). It’s also called NSAID‑exacerbated respiratory disease or Samter’s Triad.

Patients often discover the syndrome after years of unexplained attacks, so early recognition can spare a lot of frustration. Aspirin-Exacerbated Respiratory Disease affects roughly 9% of adults with asthma and up to 30% of those who also have nasal polyps.

Who Is Most Likely to Develop AERD?

Typical onset occurs between ages 20 and 50, without a clear genetic cause. The condition is more common in females and in people of European ancestry, but studies show significant diagnostic delays for Black and Hispanic patients-often three years longer than for White patients.

- Prevalence: about 1.2 million adults in the United States.

- Age of onset: 20‑50 years.

- Gender: slight female predominance.

- Comorbidity: 100% have nasal polyps, 90%+ have chronic sinusitis, and 70‑80% report severe asthma.

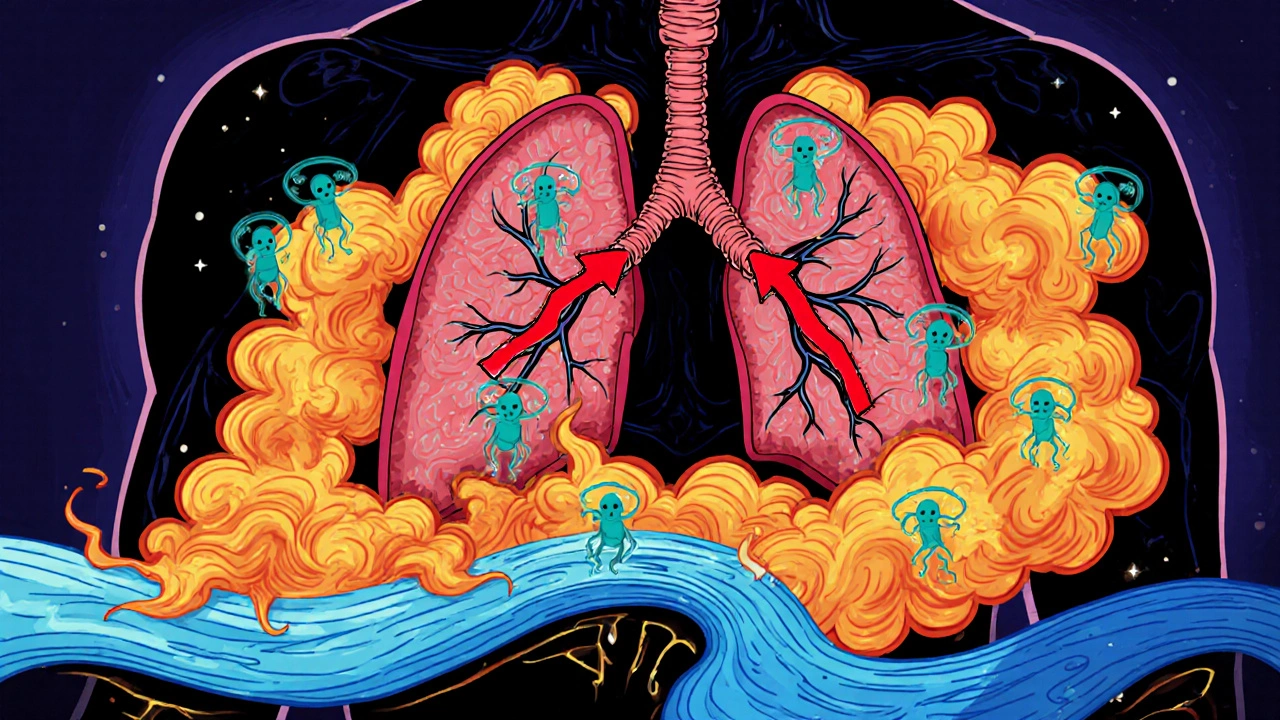

How AERD Works - The Underlying Biology

At the heart of AERD is a disruption of the cyclooxygenase‑1 (COX‑1) pathway. When COX‑1 is blocked by aspirin or most NSAIDs, the body diverts arachidonic acid toward the leukotriene route, spiking levels of leukotriene E4. At the same time, production of the protective prostaglandin E2 drops, removing a natural brake on inflammation.

This chemical imbalance fuels a strong Type 2 inflammatory response-high IL‑4, IL‑5, and IL‑13-drawing eosinophils into the airways and sinus tissue. The result is chronic swelling, mucus over‑production, and the rapid regrowth of nasal polyps after surgery.

Symptoms That Signal the Triad

Upper‑respiratory signs dominate the picture:

- Persistent nasal congestion (98% of patients).

- Large, recurrent polyps (100%).

- Loss of smell or reduced sense of smell (over 90%).

- Frequent sinus infections (≈85%).

Lower‑respiratory complaints stem from asthma:

- Wheezing (78%).

- Chest tightness (72%).

- Coughing (83%).

- Shortness of breath (65%).

When a patient takes aspirin, ibuprofen, naproxen, or any COX‑1‑inhibiting NSAID, symptoms flare within 30‑120 minutes, often with a sudden headache, red or watery eyes, and a sensation of throat tightening.

Alcohol can trigger a similar, though usually milder, response in about three‑quarters of patients, sometimes after just one drink.

Diagnosing AERD - What Doctors Look For

The classic clinical picture-adult‑onset asthma, chronic sinus disease with polyps, and NSAID sensitivity-is usually enough to raise suspicion. Confirmatory steps often include:

- A detailed medication history focusing on aspirin and NSAID reactions.

- Baseline spirometry to gauge asthma severity.

- CT imaging of sinuses to document polyp burden.

- An aspirin challenge test in a controlled setting, which reproduces symptoms after incremental dosing.

Because many primary‑care physicians miss the alcohol‑sensitivity clue, patients may endure years of misdiagnosis. Studies show an average diagnostic lag of 7‑10 years.

Standard Management Options

Effective care hinges on three pillars: avoiding triggers, controlling inflammation, and, when possible, modifying the disease’s underlying pathway.

Avoidance Strategies

Simple but crucial: steer clear of all COX‑1‑inhibiting NSAIDs. Many patients switch to acetaminophen, which is generally safe, but always double‑check with an allergist. Alcohol moderation is also advisable for those who notice reactions.

Pharmacologic Therapies

Below is a quick side‑by‑side look at the most widely used options.

| Therapy | Mechanism | Typical Efficacy | Key Drawbacks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aspirin Desensitization | Gradual exposure to aspirin to induce tolerance | Improves asthma control in ~85% and cuts sinus surgery need by 60% | Requires 2‑3 day inpatient stay; daily high‑dose aspirin lifelong |

| Dupilumab (Dupixent) | IL‑4Rα antagonist (blocks IL‑4 & IL‑13) | Reduces polyp size in 50‑60%; improves asthma scores | High annual cost (~$38,500); insurance gaps |

| Leukotriene Inhibitors (e.g., MN‑001) | Blocks leukotriene synthesis or receptor | Phase 2 data shows 70% reduction in polyp recurrence | Not yet FDA‑approved for AERD; limited availability |

| Standard Inhaler Therapy | Bronchodilators ± inhaled steroids | Only 35% achieve adequate control when used alone | Doesn’t address underlying COX‑1 pathway |

Aspirin Desensitization - The Gold Standard

Performed in specialized allergy centers, the protocol starts with a tiny aspirin dose, doubled every 30 minutes until a target of 325 mg is reached. Patients then stay on a maintenance regimen-commonly 650 mg twice daily-for life. Success rates hover around 90% when patients adhere strictly to the regimen.

Potential side effects include gastric irritation, bleeding risk, and occasional worsening of asthma symptoms during the initial escalation phase. Co‑prescribing a proton‑pump inhibitor can mitigate stomach issues.

Biologics - Targeted Immune Modulators

Dupilumab, the most studied biologic for AERD, blocks the IL‑4/IL‑13 axis, curbing the type 2 inflammation that fuels both asthma and polyp growth. It’s administered via subcutaneous injection every two weeks.

While hugely effective for many, the price tag restricts access, and some patients still need sinus surgery despite therapy.

Emerging Leukotriene‑Focused Drugs

MN‑001 (lodadustat) is a novel leukotriene synthesis inhibitor that received FDA breakthrough designation in 2023. Early trials report dramatic drops in polyp regrowth and fewer NSAID‑triggered attacks. If approved, it could become a third pillar alongside aspirin desensitization and biologics.

Living with AERD - Lifestyle Tips

Beyond medication, everyday habits make a big difference:

- Medication diary: Log every drug, dose, and reaction. Patterns become obvious fast.

- Carry an “AERD Card” that lists safe meds (acetaminophen, certain antihistamines) and warnings against NSAIDs.

- Stay hydrated and use saline nasal rinses to keep sinus passages clear.

- Discuss any upcoming surgeries with your allergist; pre‑operative aspirin desensitization can reduce post‑op polyp recurrence.

- If alcohol triggers symptoms, limit intake and observe the effect of different beverages.

Patient Journey - Common Roadblocks

Many patients describe a maze of specialists: ENT, pulmonology, allergy, and sometimes gastroenterology. The average pathway involves 4-6 educational sessions (8-12 hours total) before a clear plan emerges.

Accessing a center that offers aspirin desensitization is a hurdle-only about 12% of allergy practices provide it. Travel to a specialty hub can add cost and time, but the payoff is often fewer sinus surgeries and better asthma control.

Looking Ahead - Research and Future Therapies

The AERD Research Consortium, funded with a $5.2 million NIH grant, is building a national registry tracking 2,000 patients over five years. This database will accelerate discovery of genetic or biomarker signatures that predict who will respond best to which therapy.

Precision‑medicine approaches targeting specific inflammatory pathways (e.g., IL‑33 blockers) are projected to slash sinus‑surgery rates by up to 40% by 2028. Meanwhile, broader awareness campaigns aim to cut diagnostic delays, especially in minority communities.

Quick Checklist for Patients and Clinicians

- Confirm the triad: asthma + nasal polyps + NSAID reaction.

- Refer to an AERD‑specialized center for an aspirin challenge.

- Consider aspirin desensitization as first‑line long‑term therapy.

- Evaluate biologics (dupilumab) if desensitization isn’t feasible or if disease remains uncontrolled.

- Stay alert to alcohol‑related symptoms and keep a symptom diary.

- Use saline irrigation and nasal steroids to control upper airway inflammation.

- Schedule regular follow‑ups to reassess lung function and polyp status.

What is the difference between AERD and ordinary asthma?

AERD includes the classic asthma symptoms but adds chronic sinus disease with nasal polyps and a specific sensitivity to aspirin and COX‑1‑blocking NSAIDs. This triad shapes both diagnosis and treatment, which differs from typical asthma that doesn’t involve the sinus component or drug reactions.

Can I take ibuprofen if I have AERD?

No. Ibuprofen blocks COX‑1 and will likely trigger the same respiratory flare‑ups as aspirin. Acetaminophen is generally safe, but always confirm with your allergist.

How long does aspirin desensitization take?

The initial desensitization protocol usually requires a 2‑ to 3‑day inpatient stay. After reaching the target dose, patients continue on a daily aspirin regimen indefinitely.

Are biologic drugs like dupilumab covered by insurance?

Coverage varies. About 38% of AERD patients report full insurance support for dupilumab. It’s best to check with your provider’s pharmacy benefits manager and explore patient‑assistance programs.

Does alcohol always trigger a reaction in AERD?

Roughly 75% of people with AERD notice some level of nasal congestion or facial flushing after drinking. Sensitivity varies; even a single drink can cause symptoms for some, while others only react to larger amounts.

There are 8 Comments

Kasey Marshall

AERD is a mix of asthma nasal polyps and NSAID sensitivity. Avoid aspirin ibuprofen and other COX‑1 blockers if you have it. See an allergist for an aspirin challenge test. Dupilumab can help but check your insurance coverage. Aspirin desensitisation often reduces surgery need. Keep a medication diary to track reactions.

Monika Pardon

Oh, thank you for illuminating the obvious that aspirin is a mortal enemy to anyone with AERD. It is truly astonishing that the medical establishment has kept this secret from the masses for decades. One would assume that the pharmaceutical conglomerates are eager to hide the fact that COX‑1 inhibition unleashes a leukotriene storm, yet they smile and push aspirin advertisements. The notion that a simple over‑the‑counter pill could provoke such a dramatic immune response is, of course, part of a larger scheme to keep us dependent on expensive biologics. I am convinced that the push for dupilumab is orchestrated by the very same entities that profit from our ignorance. Meanwhile, the real solution-avoiding COX‑1 inhibitors and maintaining a meticulous drug diary-remains buried beneath layers of corporate spin. It is almost comedic how quickly we accept high‑cost injections while dismissing low‑tech avoidance strategies. In the end, the only thing we need is to stay vigilant and question every label. Remember, the greatest danger often wears a familiar white cap.

Jennyfer Collin

The recent establishment of the AERD Research Consortium, funded by a substantial NIH grant, represents a pivotal advancement in deciphering the genetic underpinnings of this condition. By aggregating data from two thousand participants, the registry endeavors to identify biomarkers predictive of therapeutic response. Such an initiative, however, cannot be viewed in isolation from the broader context of pharmaceutical interests seeking to monetize targeted interventions. While the prospect of IL‑33 blockers reducing surgical rates is promising, one must remain circumspect regarding the potential for market‑driven research agendas. Nonetheless, the collaborative effort across academic centers offers a rare opportunity for transparent data sharing. It is incumbent upon clinicians and patients alike to scrutinize the methodology and ensure that findings are disseminated without corporate distortion. Ultimately, robust, unbiased evidence will empower clinicians to tailor treatment strategies beyond the conventional reliance on aspirin desensitization and biologics. The scientific community must guard against the subtle encroachment of profit motives that could compromise patient care.

Tim Waghorn

Aspirin‑Exacerbated Respiratory Disease constitutes a distinct clinical phenotype characterized by the triad of asthma, chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps, and hypersensitivity to cyclooxygenase‑1 inhibitors. The pathogenesis originates from an enzymatic imbalance wherein inhibition of COX‑1 diverts arachidonic acid metabolism toward the 5‑lipoxygenase pathway, resulting in elevated leukotriene E4 concentrations. Concomitantly, prostaglandin E2 synthesis diminishes, removing an endogenous anti‑inflammatory brake. This biochemical shift precipitates a type‑2 cytokine cascade marked by increased interleukin‑4, interleukin‑5, and interleukin‑13, which recruit eosinophils to the airway and sinus mucosa. Histopathologic examination frequently reveals eosinophilic infiltration alongside subepithelial edema. Clinically, patients present with refractory asthma symptoms, persistent nasal congestion, and rapid polyp regrowth after surgical intervention. Diagnostic evaluation should commence with a thorough medication history to identify NSAID‑related exacerbations. Baseline spirometry and sinus computed tomography provide objective measures of lower and upper airway involvement, respectively. When suspicion remains high, an aspirin challenge performed under controlled conditions confirms the diagnosis. Management is multifaceted, beginning with strict avoidance of COX‑1‑inhibiting agents. Aspirin desensitization, administered in a monitored setting, has demonstrated efficacy in reducing exacerbation frequency and surgical requirements. Biologic agents targeting the interleukin‑4/13 axis, such as dupilumab, offer additional therapeutic benefit, albeit tempered by cost considerations. Leukotriene receptor antagonists may provide adjunctive control, yet their role remains investigational in this population. Long‑term follow‑up should incorporate periodic assessment of pulmonary function and endoscopic evaluation of sinus disease. Ultimately, a personalized approach that integrates avoidance strategies, pharmacologic therapy, and, when appropriate, desensitization yields the most favorable outcomes for patients with AERD.

Brady Johnson

Reading the latest AERD guidelines feels like watching a tragedy where the hero is a $38,500 injection and the villain is a cheap aspirin tablet. The pharmaceutical elite parade dupilumab like a miracle while dropping the ball on low‑cost desensitization programs. Patients are forced into a perpetual cycle of hospital visits, insurance denials, and endless paperwork. Meanwhile, the real culprits-big‑drug profit motives-remain hidden behind polished press releases. It’s infuriating to witness science reduced to a bidding war where the highest bidder dictates care. Until we dismantle this exploitative model, sufferers will continue to pay the price both financially and physiologically.

Jay Campbell

I’ve found that keeping a simple medication diary and sharing it with your allergist can streamline the treatment plan. It’s a modest step that often leads to clearer decisions.

Laura Hibbard

Wow, you really captured the drama of the healthcare system-thanks for the roller‑coaster ride. If anyone needed a reminder that we can still take charge, consider this: start with that diary you mentioned, avoid COX‑1 blockers, and if dupilumab is out of reach, explore aspirin desensitization at a nearby center. Small actions add up, even when the big players try to keep us in the dark.

Rachel Zack

People should stop ignoring the warning signs and take responsibility for their health.

Write a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *